High Country Apps Colorado Rocky Mountain Wildflowers

A well thought-out app that pros and beginners alike can use to identify most of the hundreds of species of wildflowers, trees, and shrubs in the central Rocky Mountains and nearby ranges.

Pros

- Nearly comprehensive coverage of species in the target region

- Searchable by common and scientific species and family names

- Random access searching by a broad range of characteristics

- Multiple color photos of each species

- Text descriptions, range maps, and additional info

- Price

Cons

- Could combine family and characteristics searches

- Text descriptions are rather technical for the layman

As a card-carrying botanist (my BSc is in botany) one of my main ways of relating to the natural world is by paying attention to the local flora, wherever and whenever I am. Depending on how far the where is from familiar botanical territory, whether or not the when is at a time when plants are in bloom, and just how darn many plants there are out there to ID, this can be a more or less challenging task.

High summer in the Rocky Mountains, with its vibrant show of forest, meadow, and the alpine wildflowers, is a prime time and place for me to practice that craft. I have had the great pleasure of spending chunks of my last two summers witnessing that great show, first on a 10-day hike in the Wind Rivers, then in a month of working and recreating at and around the Rocky Mountain Biological Lab near Crested Butte.

The Rocky Mountain Wildflowers app was on call, in my pocket, the entire time, and helped me to ID probably 120+ species of wildflowers and a few trees and shrubs as well.

This is the best of several botanical apps that I have used, and has advantages over a traditional, “analog” field guide on several fronts. It covers 529 species, and it was only rarely that I failed to track down whatever flower was in front of me because it wasn’t on that list.

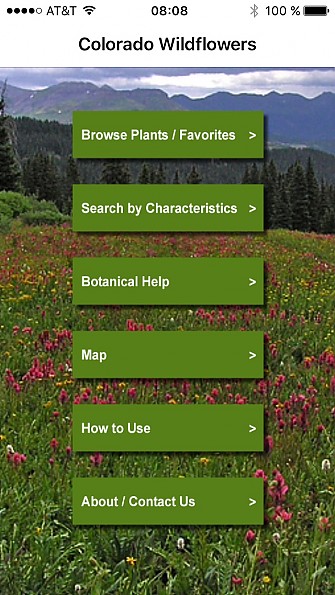

The home screen offers two paths for finding your flower. The first, “Browse plants/favorites”, includes a text search engine. Scientific names, common names including some variants, and family scientific and common names are all indexed. As an experienced botanist, I often recognize the family, and less experienced users can quickly learn to recognize a few easy families such as Apiaceae (carrot or parsley family, with flat-topped, umbrella-like flower clusters) or Fabaceae (pea family, with distinctive, bilaterally symmetrical flowers; lupines, for example). Depending on the size of the family, this can provide a powerful shortcut. And if you already recognize your plant as a lupine (Lupinus), you can just go straight to those, using either spelling.

It is also possible to simply browse through the whole list in one of four modes: common name, scientific name, scientific family name, or common family name. That’s not a very efficient way to find a flower in a list of 529 species, but becomes much more so if you can whittle the list down to somehere between a handful and a few dozen candidates.

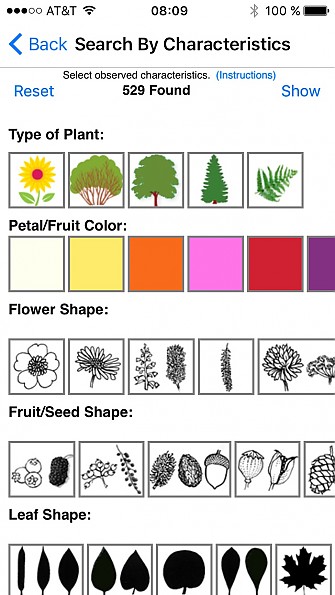

(this screenshot does not show the full range of options; you can scroll both horizotally and vertically to see them all)

That’s where “Search by Characteristics”, the second mode of finding your flower, comes in, and where the main advantage of app over book emerges. Each species is also indexed by no less than a dozen other characteristics, including easy ones such as plant type (wildflower, shrub, tree, etc.), leaf shape, or flower color and somewhat more technical but potentially useful features, such as fruit/seed shape or leaf/stem texture (hairy, shiny, leathery, etc.); habitat and elevation are also included as search criteria. These are offered up as lines of icons with diagrams or descriptive text – just go down the list and tap on a few obvious choices. By selecting among these you can quickly narrow the list down to a relative few species, then tap Show to browse through the shortened list to find your flower.

There’s no need to specify all or even most of these characteristics—just three or four may be enough to get the candidate list to browseable size. As you make you selections, some small text appears above the icons to help you confirm that you are making a good choice (“Flowers in ball, flat top, or umbrella shape (sunflowers, parsleys)”) Where there is some ambiguity, species may be double-listed. For example, if a species can be found with either white or purple flowers, or if you are not whether it is subalpine or alpine, you will find it under both. And if you’re uncertain if your plant is small or medium size, it’s easy enough to try it both ways or just leave it out and go with other, more reliable characteristics.

This random access approach allows a level of flexibility that you won’t find in printed field guides, which are often arranged hierarchically, typically with flower color (which can sometimes be ambiguous) as the first choice. Instead you can access each species by any one of many different pathways.

Once you have a candidate, you can begin confirmation by looking at photos. Most species are represented by at least two and sometimes as many as five photos. Usually there is at least a close up of the flowers and a pulled-back shot showing the whole plant so you can see leaves and stem as well. Sometimes there is a simple black and white diagram to help show some key characteristics. In contrast, many photographic field guides have only a single photo of each species, usually focused on the flowers and often leaving leaves out completely.

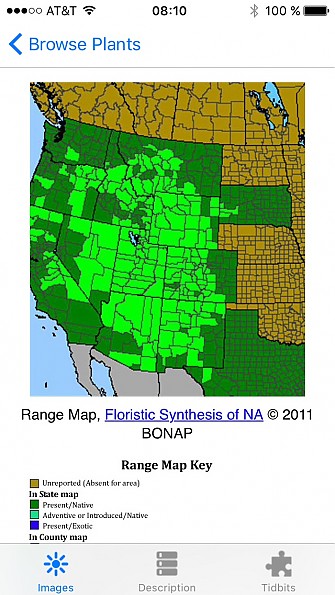

Below the photos there is a range map that can help confirm that your suspect is where it’s supposed to be. The maps are imprted from an open access, technical manual, show distribution in the western states at county level, and are reproduced with a legend to help decode all the colors.

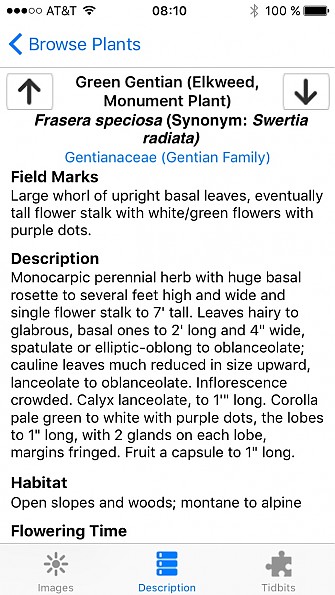

For further confirmation, you can tap on the Description icon at the bottom of the screen to proceed to a moderately technical description of the plant that includes notes on habitat, flowering time, and similar species. You would have to back up to the glossary to decode some of the botanical terms, and unfortunately your species search will be forgotten in the process. Hopefully the photos will be good enough for a positive ID.

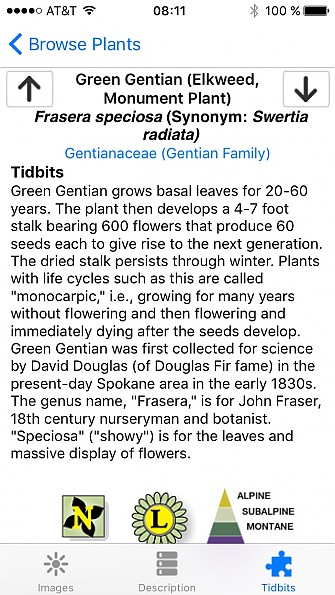

A third page, Tidbits, gives a less technical description of a few key characteristics, other common names, usually some etymology of the scientific name, and other comments on the plant’s ecology or human uses. It also shows the criteria used to classify the plant in the characteristics database.

A third page, Tidbits, gives a less technical description of a few key characteristics, other common names, usually some etymology of the scientific name, and other comments on the plant’s ecology or human uses. It also shows the criteria used to classify the plant in the characteristics database.

Users would be well advised to get to know the app via the How to Use and Botanical Help sections available from the app's home page. The former defines some of the characteristics, vegetation zones and the like, the latter introduces plant families, the basics of flower structure and leaf shape and arrangement, and will lead you to an extended glossary of botanical terms. The about page also includes some useful information.

The rather artful general Map shows the geographic area covered by the guide, which spills over from Colorado into southern Wyoming, northern New Mexico, and the mountains of eastern Utah. One of the advantages of this guide is that it doesn’t try to cover too much territory—its focus on Rocky Mountain species keep the overall list of plants to manageable size. I have tried out other ID apps and books that bite off much bigger chunks of territory, usually by leaving out many species that may be found in the target region, leading to frustration when you are trying to look up something that isn’t in the book.

All of this adds up to the best of the several plant ID apps I have tried in various parts of the country. I have paper field guides that weigh in at anywhere from 200 grams to nearly 1 kilogram. For those of us that are already carrying smart phones for photo, GPS, bedtime reading, or many other functions, there is essentially no weight penalty for adding in a plant ID app (or two or three). It’s also considerably less expensive than any equivalent paper filed guide.

It takes up about 200 MB of space on my iPhone, and doesn’t require an internet or data connection—it’s all there. I leave my phone on for day trips, but on longer trips I may turn it off during the day and just collect a few specimens as I go for ID when I get to camp. A good backup battery, still weighing less than many of those field guides, will go a long way towards extending the usability of this and other apps.

What could be better? I would like to be able to combine search modes by specifying the family and then choosing some key characteristics. If I’m pretty sure I’m looking at a white mustard family flower, I’d like to be able to go directly to that family and maybe narrow it further by specifying flower color and a few other characters.

The character list could also include the number of flower petals, which works well at least for larger flowers where these are easily counted. For example, mustards and the green gentian above have four petals, which is rather unusual and therefore a good way to home in on these species.

Source: $9.99 at the Apple app store, also available on Android