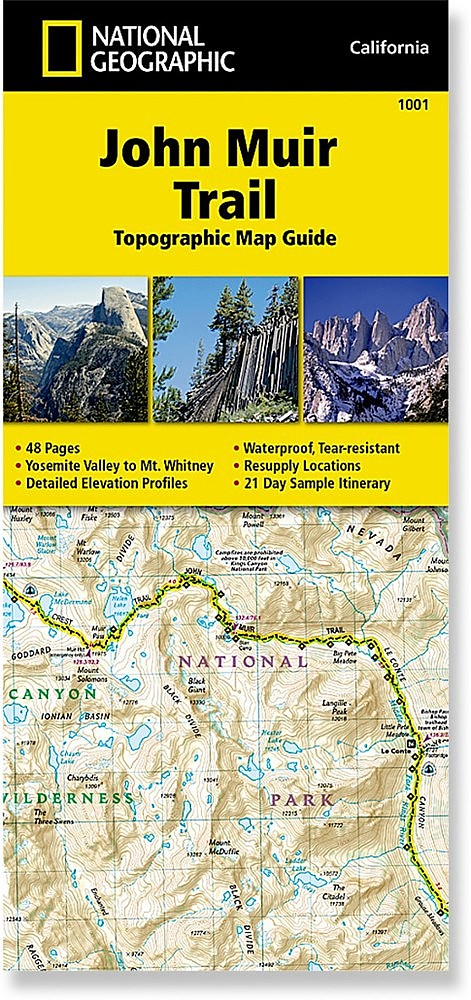

National Geographic John Muir Trail Topographic Map Guide

If you are contemplating thru-hiking the John Muir Trail (or any section of it), this John Muir Trail Topographic Map Guide does an excellent job of gathering all the needed information for planning, plus having detailed maps of the entire trail and surrounding terrain.

Pros

- Detailed map guide to the John Muir Trail

- Small size (fits in pocket of shell jacket)

- Lightweight compared to other options

- Waterproof and tear resistant

- Accurate mileages to waypoints along the trail

- Includes resupply points with shipping info

- Includes trail profiles

Cons

- Information on permit procedure is somewhat sparse (need to go online to get details)

- Details are tiny, requiring good eyes or better glasses for us old geezers

- Grid is UTM/MGRS, so the Mercator flattening produces some distortion that lat/lon would reduce

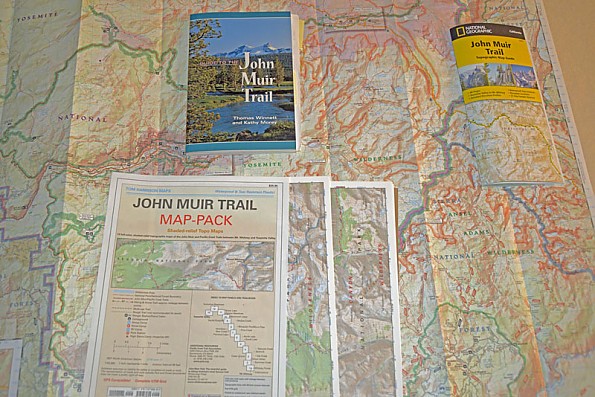

Comparison of size of National Geographic Yosemite map with the John Muir Trail Topographic Map Guide (USGS 1:250,000 map in background)

Background:

I have to confess up front that, despite having hiked and climbed on all seven continents, including fairly extended expeditions (both time and distance), and having lived in California for a total of roughly 50 years (minus short sojourns in Massachusetts and Mississippi), I have not thru-hiked the entire length of the John Muir Trail, although I have hiked major portions.

The northern section from Happy Isles (the north terminus) to Tuolumne Meadows and a few miles beyond played a crucial role in my wife’s and my lives, as did a life-changing event in the section between Thousand Island Lake and Devil’s Postpile.

I also have hiked with friends and fellow climbers over some of the southern section to climb Mt. Whitney (the southern terminus) and other technical climbs in Kings Canyon and Sequoia NP, plus various sections in between, approaching across both the steep eastern flank of the Sierra and the more gentle western side. I have never totaled up what fraction of the 211 miles of the full trail I have set foot on, but know it is about half the distance.

However, I have done treks elsewhere that totaled as much as the JMT in terms of distance and time, including long portions of the PCT. I do have UL gear, though most of my hikes have included a huge load of climbing gear. My interests are primarily mountaineering and technical rock climbing, along with backcountry skiing and ice climbing. Strange as it may seem after reading this, I find the Sierra Nevada to be my favorite wilderness.

Between Barbara and me, we have accumulated a huge number of maps (most well-worn) of places we have gone on the seven continents. As a staff member of the local High Adventure Training course for my local Boy Scout Council, I spend a lot of time teaching map and compass (plus electronic widgets) usage to help people who do thru-hikes. We have planned to do the full JMT several times, but other things got in the way.

Several decades ago, a small startup company which had developed an electronic mapping program on what we now consider a very primitive electronic computer, approached me and asked me to evaluate their program. I had no formal affiliation with them (and didn’t get paid either). As they grew, they suffered the fate of many startups in Silicon Valley, being bought by a larger organization, the National Geographic Society.

Last summer, at the Outdoor Retailer Show, I wandered into the NGS booth. One of the original members of that little company (now an executive with NatGeo) asked if I would be interested in trying out their new booklet, a publication from National Geographic, a Topographic Map Guide to the John Muir Trail. Since Barbara and I still plan to do the JMT, and the small size of the booklet looked like it had its benefits, I took the guide mostly just to see what it was like. I already have books and maps of the JMT aplenty.

After we got home with way too much swag from the show, we were tossing out most of the handouts and other junk, when I picked up the booklet and decided to take a further look. I noticed that the official price is $14.95, vs the $11.95 price of the separate Trails Illustrated maps (many of which we have bought over the years to cover the same area).

The JMT is a well-travelled and well-maintained trail, generally easy to follow during most of the year. There are several books and map packages of the JMT. Still, there are branch trails that people have taken mistakenly, and there are branch trails to resupply points for thru-hikers (most people take three to four weeks to hike the full 211 miles). Still, planning is a good idea.

There is a long tradition of using the excellent Tom Harrison maps. Before Harrison came out with his maps, your choice was to carry a huge stack of USGS quads — 30’ scale quads in my high school years, 15’ quads when I was in college, and eventually 7’.5 quads. The USGS maps were on a basic paper, so that the introduction of waterproof, tear resistant Harrison maps was a big leap forward. Another plus was that the Harrison maps fully covered the JMT (plus including the sections of the PCT that are partially coincident with the JMT). This brought the weight and size way down, plus you did not have the worry about the paper USGS maps disintegrating when thoroughly soaked (that changed with time as well).

The books about the JMT are bulky and have hard to use maps. In the 1980s, you could get Trails Illustrated maps on waterproof paper. But these only covered the National Parks and Forests — so still a small bundle of maps to cover the whole trail. Besides, GPS was not available yet (for civilians anyway).

When the Harrison maps came out, they had a UTM/MGRS grid, though there were lat/lon tick marks on them. Many people like the UTM grid since the scale is denominated in metric distances. But the UTM (and the military version MGRS) uses a Mercator projection, which is a flattening of the spherical Earth. This results in the grid having discontinuities in the numbering system from one UTM zone to the next in the east-west direction (or, to use the correct terminology, Easting).

As it happens, one of the UTM zone boundaries runs up the Sierra, so that if you are using that system, you must think a bit about the jump in the numbers if you are using the Mercator scales. Latitude and longitude, on the other hand, fits nicely over the spheroidal planet we live on. Remember, the coordinates are simply like a street address, so you don’t really have to convert the numbers – just count the blocks and “house numbers”. One other thing about the Harrison maps is that they were on the NAD27 datum, where more recent maps are the more accurate NAD83 datum.

One book, now in its 3rd edition, is Winnet and Morey’s Guide to the John Muir Trail. It contains a huge amount of good (and very detailed) information — sometimes almost leading you by the hand along the trail. It has maps, but of small scale (that means the details are small, and cover large areas) and colored in a scheme that is harder to read than the USGS, Harrison, or National Geographic Trails Illustrated maps

The photo below compares the size of the new National Geographic Society John Muir Trail Topographic Map Guide (upper right) to the Winnett and Morey book, Harrison maps (lower center), and an unfolded Trails Illustrated map of Yosemite National Park. Most of the Topographic Map Guide is exactly that – all maps. There are, however, 10 pages packed with detailed information.

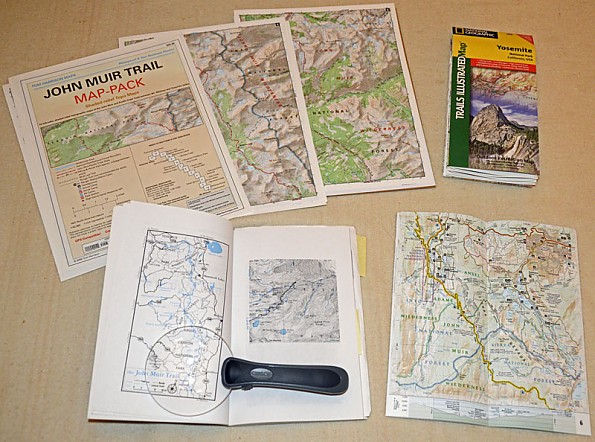

This photo compares the Harrison maps (top left), the folded Yosemite map (top left), the maps in the Winnett and Morey Guide, and the new National Geographic John Muir Trail booklet opened in the lower right.

Details:

All the materials I have pictured and described so far have valuable information that the would-be JMT thru-hiker can use. The question is what are the tradeoffs if you use the new, compact John Muir Trail Topographic Map Guide. As I started digging through the pages, comparing details included in the new Guide with the larger books and maps, I was reminded that the various sources of maps have a wide variation in the scales used. During my years of backpacking, I have used 30’ (1:125,000), 15’ (1:62,500), and 7.5’ (1:31,250) maps from the US Geological Service.

The map scale of the TMG is approximately 1:63,360, the same as the Harrison maps and many US Forest Service maps. This is conveniently 1 inch to the mile. The map grid is the UTM/MGRS grid, which means that the scale changes slightly from north to south (a consequence of using a Mercator projection to “flatten” the Earth’s surface). However, each of the map pages have lat/lon tic marks on the boundaries of the map.

For comparison, the NatGeo Trails Illustrated maps which cover the JMT (Yosemite, Sequoia/Kings Canyon, Whitney, etc) also use the 1:63,360 scale, sacrificing compactness and weight for more detail.

The Topographic Map Guide has a listing of the latitude and longitude, as well as UTM data, of significant landmarks along the trail. National Geographic also has a GPX waypoint file that is a free download which can be either lat/lon or UTM. Note that this is 61 waypoints. The waypoints are marked on the Guide’s maps with a purple arrow.

If you are using a GPS receiver to follow the trail continuously, you will find that you will either need a large supply of batteries or will need to carry rechargeable batteries and a small solar panel. However, as I tell the students in my land navigation courses, if you pay attention to the trails as you hike them, you only need to turn on your GPSR a few times during the day, at rest stops or at your evening campsite.

Because the booklet is sized to fit conveniently in a pack pocket, and to include as much detail information as possible, print size and many details are quite small. Since I am now past the ¾ century mark, I have to use bifocals (or use one of the clip-on “flip” magnifiers) to read all the detail. This is not a serious problem, just inconvenient at times.

Details of testing:

Having hiked a number of segments of the JMT and Pacific Crest Trail, I am familiar with what the trail is like for most of its length. Not having time to do the entire trail for this review with the Topographic Map Guide in hand, I decided to revisit the northern-most few miles. For those not familiar with the JMT and PCT, these two “long trails” are the same or more or less parallel for the section through the Sierra Nevada. The big difference is that the PCT includes a long approach from the US/Mexican border on the south end, and then continues northward from Yosemite Valley to the Canadian border.

The booklet has a detailed listing of the wilderness regulations close to the front, along with a summary of Leave No Trace Backcountry Ethics. In this day and age of huge demand on getting to the hills, forests, and the outdoors in general, it is vital that we all practice Leave No Trace. You will be required to use a canister — the bears in Yosemite and other places along the trail have learned how to retrieve counter-balanced bear bags as well as how to get into certain canisters and Kevlar soft bags. There are a few campsites that have steel lockable containers.

The booklet does have a summary of the agencies and reservation requirements, as well as the locations, phone numbers, and websites of the Permit Offices. As I have already mentioned, with the ever-changing requirements, using the online information will give you the latest regulations. Count on applying for your permits a half year in advance of your trip if you plan on hiking a long section of the JMT.

The resupply locations and shipping information (for sending your food re-supply in advance) are included. A warning from several friends who have done the hike — you will have to pay a “storage” fee at several of the re-supply locations. But the different locations calculate the fee differently (one charged a friend from the shipping date, not from the date the box arrived at the location, an additional 10 days). Be prepared to hold the location to its published method of charging.

Below are several photos in the northernmost section between the start of the JMT at Happy Isles in Yosemite Valley and the part of the trail between Tuolumne Meadows (a 2- to 3-day hike from Happy Isles) to several miles south of Tuolumne through Lyell Canyon to Donohue Pass (the northern 36 miles of the JMT).

One thing I noted when I was taking the photos above was how much the tree coverage has increased since I last hiked on the northern section of the trail.

Barbara and I had planned to do a longer section of the trail using the National Geographic Topographic Map Guide. However, the stricter rules that have come into effect during the past couple of decades have required either applying a half year or more in advance, even for short sections, or arriving a day or more in advance and chancing getting a “walk-in” permit.

The “Walk-ins” require you get in line before 11 a.m. at one of the designated stations. If all the permits for the day have been handed out, you might be able to get one the next day, or the next or… Walk-in permits allow you one night of camping, although most of the designated campsites require reservations. You can do a day hike, as long as you are back before sunset. I ended up doing just a day hike out of Tuolumne. Going with a very light daypack did allow me to cover about 15 miles car to car and a bit of photography.

This photo-hike showed up one of the deficiencies of the Topographic Map Guide, namely that the permit process is poorly described. However, as my discussion with the rangers at the permit office demonstrated, this is really not a fault of the booklet. The permit availability and rules change from season to season. Your best bet is to go online and/or make contact with Yosemite or the Whitney ranger station for full length hikes or the intermediate stations for section hikes. Start the process at least six months or more before your hoped-for time window.

The guide itself is 48 pages of waterproof, tear-resistant material. You can drop it into the lake or a stream (not recommended, since you might have a hard time retrieving it from the more powerful streams) without affecting the readability of the maps and descriptions. However, there is a caution posted in the booklet to avoid contact with petroleum products such as solvents, gasoline, stove fuel, and sunblock, since these can smear the ink. Also, if you get the booklet damp and let the moisture freeze, it is a good idea to thaw it before bending the pages or pulling them apart. I did test the waterproofness by holding the book under a water faucet.

The trails are complete not only for the JMT itself, but for the numerous side trails, resupply locations, and the elevation profiles (Harrison and the guide books lack the profiles). A sample 21-day itinerary is included.

Personally, I am not sure of the helpfulness of the sample itinerary for most through-hikers because everyone has his/her own pace, different ideas of how much gear to carry, and the changes you will inevitably encounter from year to year. The changes that are taking place in the climate are already affecting the planning of many experienced and inexperienced hikers (the sample itinerary is prefaced by a reminder to give yourself plenty of time for the length of the trail and the variability of the weather).

Conclusions:

As someone who has used maps for decades, I have to say this is one of the cleverest ideas for packing a huge amount of useful information into a small and durable package. While anyone planning to do the JMT should do plenty of research in books like the Winnet and Morrey guide, as well as online (particularly contacting the National Park Service and National Forest Service with respect to the current regulations and permit rules to get the latest changes), the TMG comes the closest of any source to collect everything needed in a single 3-ounce/88-gram package. The Winnett-Morey book weighs a half pound, and the full set of Trails Illustrated maps even more than that.

Considering that the average JMT thru-hiker takes three weeks or more, which requires 40 pounds of food, anything that saves weight is greatly appreciated by trip’s end. You can make use of the resupply points, all listed in the TMG. Or you can have friends bring the new supplies to you on the trail (it is illegal to cache the food along the trail in advance).

Source: received it as a sample, freebie, or prize (Handout at the Outdoor Retailer Show)

Your Review

Where to Buy

You May Like

Specs

| Price |

MSRP: $14.95 Current Retail: $14.95 Historic Range: $14.95 |