Cammenga Tritium Lensatic Compass 3H

Original Review: April 6, 2012

Well-made, but less than ideal for non-military users.

Pros

- Air-filled compass housing can't develop a bubble

- Self-luminous tritium lighting (in some models)

- Excellent manufacturing and assembly quality

- Deep-well compass housing for use in multiple magnetic zones

Cons

- Mediocre accuracy

- Mediocre shock resistance

- No protractor base for taking bearings from a map

- Degree scale in 5-degree increments only

- Can fog over in certain conditions

- Floating compass dial slow to settle

The U.S. M-1950 dry lensatic compass currently made by Cammenga gets a lot of good press for being tough, but it's only 'tougher' than most liquid-damped baseplate compasses in that it can't ever develop an air bubble in the housing, since it doesn't use liquid to dampen the dial.

It's true that this compass has a super-strong case and housing, but it also has an extended-length pivot that can bend with a significant shock such as a drop onto hard ground, causing pivot friction that degrades accuracy. Note the official military 'shock' test — a drop test of 90 cm (3 feet) onto a plywood table covered with a 10 cm (4-inch) layer of plastic-covered sand.

This compass is often praised for its superior accuracy over most baseplate style compass designs in shooting an azimuth (taking a bearing) to an objective or landmark. Let's examine that.

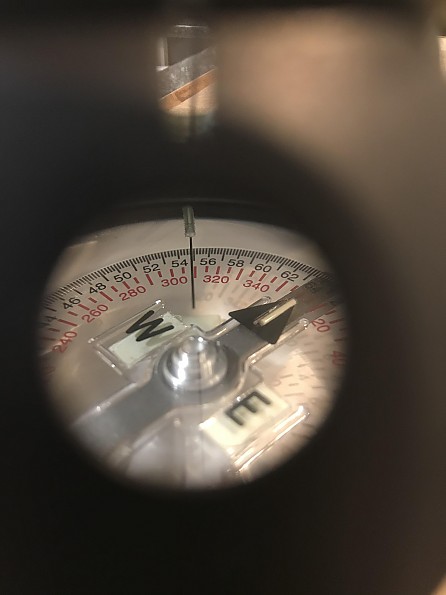

The compass dial is in both mils and degrees, and as the military uses mils, the degree scale is given second place on the dial. As a result, the degree scale is only marked in large five-degree increments — a dial you'd expect on a $10 compass, not one costing $50 or more.

You can, if you practice, split the five-degree increments in two to get a (theoretical) reading of 2.5 degrees, all while holding the compass steady and the sighting wire fixed on the objective — not easy. Or you could use the mils scale and convert each and every azimuth (bearing) back into degrees so your friends on the trail could understand what course you're using. But who's going to bother with that?

I just don't understand why Cammenga doesn't put out a version with the degree scale on the outer edge of the dial in one- or two-degree increments for the benefit of its civilian land navigators.

Then there is the issue of inherent accuracy. Brand-new, the G.I. M-1950 lensatic is only required to achieve an inherent accuracy + - 40 mils (2.25 degrees) from actual azimuth under milspec requirements. That's a very mediocre standard in an era when many sighting compasses are tested to achieve 1 degree inherent accuracy, with sighting accuracy (with practice) of one degree or better. Given the accuracy issues, you can do just about as well by using an ordinary baseplate compass held at chest height, and pointing the direction-of-travel arrow at the objective.

The compass uses magnetic 'induction dampening' instead of the more common liquid dampening used in many baseplate compasses, which is advertised as an advantage (no way to form air bubbles or leak). But what most people don't know is that the original M-1938 U.S. Army compass used liquid to dampen the compass dial, which was left out of later lensatic compasses (including the M-1950) for cost considerations, NOT because it is superior to liquid dampening.

Since it is filled with ordinary air, the M-1950 can and does fog over in cold weather or from moisture and humidity changes in tropical regions, since the interior is not purged with inert gas like your fogproof binoculars or rifle scope. Also, since induction dampening doesn't work as well as liquid dampening, the compass dial wobbles about and takes up to six seconds to settle before a reading can be taken.

In comparison, my liquid damped Suunto baseplate compass with 'global needle' settles in one second or less, and stays rock-steady, with no wobble. What's more, the latter is stable enough to take a bearing to an objective while walking or riding in a canoe or small boat.

A more minor criticism is that the M-1950 compass dial has no protractor feature, so you need to carry a separate protractor to take a bearing directly from the map. It has no romer scales, and only one 1:50,000 metric scale, which isn't much use for USGS 1:24,000 topos. It also has no adjustable declination feature for relating all compass headings to true north. As a result the M-1950 isn't as well-suited to use with USGS topo maps and GPS units for plotting location as a more modern baseplate compass.

The compass itself is built with attention to detail and all parts on my example were well-fitted with no signs of manufacturing or assembly defects. Cammenga does an excellent job on meeting milspec standards.

The tritium sighting is a great option for low light and the occasional emergency night hike, and should be available on other compass models here in the states (outside North America, anyone can buy a Silva of Sweden 4b or 54b Expedition military compass with beta, or tritium lighting). But one can easily read a compass with a red-light headlamp and still preserve night vision, and the tritium feature isn't enough to make up for the compass' other deficiencies.

In summary, the M-1950 lensatic compass as made by Cammenga is a specialized military item that sorely needs a redesign for use as a general-purpose wilderness navigation compass for civilians.

Update: April 6, 2012

Well-made, but less than ideal for non-military users.

Pros

- Air-filled compass housing can't develop a bubble

- Self-luminous tritium lighting

- Excellent manufacturing and assembly quality

- Deep-well compass housing for multiple magnetic zones

Cons

- Mediocre accuracy

- Mediocre shock resistance

- Degree scale in 5-degree increments only

- Can fog over in certain conditions

- Compass dial slow to settle

The U.S. M-1950 dry lensatic compass currently made by Cammenga in the 3H configuration is lauded as being the toughest, most accurate compass on the market. After all, the U.S. military uses it, so it must be the best, right? Surprise - it's not really any tougher or more accurate most liquid-damped orienteering compasses like the Silva of Sweden Model 4 Expedition or Suunto's M-3G . Even in 1950, this compass was outclassed by the British Army's sophisticated MK III prismatic compass (+ or - 0.5 degree accuracy). And in the civilian world, things have changed a lot since then.

It's true that Cammenga's version of the M-1950 compass has a super-strong case and housing, and can't develop an air bubble since it's a dry card (induction dampening) design. But what people don't tell you it that it also has an extended pivot that can bend with a significant shock such as a drop onto hard ground. Once the pivot is bent, the dial will not produce repeatable, accurate readings. Note the official military 'shock' test — an easy 'drop test' of 90 cm (3 feet) onto a table covered with a 10cm (4-inch) layer of plastic-covered sand.

The M-1950 lensatic compass design is also frequently extolled for its superior accuracy over most orienteering-style compass designs in shooting an azimuth (taking a bearing) to an objective or landmark. Let's examine that.

The compass dial is in both mils and degrees, and as the military uses mils, the degree scale is given second place on the dial. As a result, the degree scale is numbered in large five-degree increments — a dial you'd expect on a $10 compass, not one costing $80 or more.

You can, if you practice, split the five-degree increment spacing in half to get a (theoretical) reading of 2.5 degrees between increments, while simultaneously holding the compass steady and the sighting wire fixed on the objective, then checking for parallax error — not easy. Or you could use the mils scale and convert each and every azimuth (bearing) you take back into degrees for the benefit of your companions (all of whom will have degree scale compasses).

But why bother, when other compasses have easy-to-read dials that can be read to 1 degree or less with ease? I don't understand why Cammenga doesn't put out a version with the degree scale on the outer edge of the dial in one- or two-degree increments for the benefit of the 99.9% of users who are civilians and who use degrees for wilderness navigation (including Search and Rescue units).

Besides that, there is the issue of inherent accuracy. Brand-new, the G.I. M-1950 lensatic is only required to achieve an inherent accuracy of + - 40 mils (2.25 degrees) from actual azimuth (milspec). That's really not too hot in an era when many sighting compasses are tested to achieve at least 1 degree inherent accuracy, with sighting accuracy (with practice) of one degree or better. Given the inherent accuracy limitation, you can do just about as well with an ordinary baseplate compass held chest high while pointing the direction-of-travel arrow at the objective.

Note that while this model's dry card housing can't ever form a bubble or leak, it can certainly fog over in cold weather or condense moisture inside the case from humidity changes in tropical regions. Why? Because the interior is filled with ordinary air instead of an inert gas like your fogproof binoculars or rifle scope.

The compass uses magnetic 'induction dampening' to settle the floating dial in 'six seconds or less'. Fine, except that in comparison, my liquid dampened Suunto compass with 'global needle' settles in less than one second, and stays rock-steady, with no wobble. Because the latter is a gimbaled design, I can even take accurate compass readings while walking or riding in a small boat or canoe.

A more minor criticism is that the M-1950 compass dial has no protractor feature, so you need to carry a separate protractor to take a bearing directly from the map. It has no romer scales, and only one 1:50,000 metric scale, which isn't much use for USGS 1:24,000 topos. It also has no adjustable declination feature for relating all compass headings to true north. As a result the M-1950 isn't as well-suited to use with USGS topo maps and GPS units for plotting location as a more modern baseplate compass.

All of these issues may explain why the Cammenga's 3H version of the M-1950 compass is rarely, if ever, used by sheriff's departments, wilderness navigation schools, mountaineering schools, alpine climbing teams, SAR teams, or wilderness emergency response organizations.

The compass itself is built with attention to detail and all parts on my example were well-fitted with no signs of manufacturing or assembly defects. Cammenga does an excellent job on meeting milspec standards.

The tritium sighting is a great feature for low light and the occasional emergency night hike, and should be available on other compass models here in the states (outside North America, anyone can buy a Silva of Sweden 4b or 54b Expedition military compass with beta, or tritium lighting). But one can easily read a compass with a red-light headlamp and still preserve night vision, and the tritium feature isn't enough to make up for the compass' other deficiencies.

In summary, the M-1950 lensatic compass in 3H configuration as made by Cammenga is a special-purpose military compass that needs a redesign to compete as a general-purpose wilderness navigation compass.

Update: August 14, 2012

Well-made, but less than ideal for non-military users.

Pros

- Air-filled compass housing can't develop a bubble

- Excellent manufacturing and assembly quality

- Deep-well compass housing

Cons

- Mediocre accuracy

- Mediocre shock resistance

- Degree scale in 5-degree increments only

- Can fog over in certain conditions

- Wobbly, slow-to-settle compass dial

The U.S. M1950 dry lensatic compass currently made by Cammenga gets a lot of good press for being tough, but it's only 'tougher' than most liquid-filled baseplate compasses in that it can't ever develop an air bubble in the housing, since it doesn't use liquid to dampen the dial.

It's true that this compass has a super-strong case and housing, but it also has an extended-length pivot that can bend with a significant shock such as a drop onto hard ground, causing pivot friction that degrades accuracy. Note the official military 'shock' test — an easy 'drop' test of 90 cm (3 feet) onto a plywood table covered with a 10 cm (4-inch) layer of plastic-covered sand.

This compass is often praised for its superior accuracy over most baseplate style compass designs in shooting an azimuth (taking a bearing) to an objective or landmark. Let's examine that.

The compass dial is in both mils and degrees, and as the military uses mils, the mils scale is placed on the outside circumference of the dial, while the degree scale is in red ink and relegated to second place on the inside, with only five-degree increments or markings — a dial you'd expect on a $10 compass, not one costing $50 or more.

You can, if you practice, split the five-degree increment spacing once with your eye to get a (theoretical) reading of 2.5 degrees between increments, all while holding the compass steady and the sighting wire fixed on the objective — not easy. Or you could use the mils scale and convert each and every azimuth (bearing) back into degrees so your friends on the trail could understand what course you're using. But why bother, when there are other compasses out there with dials that can be easily interpolated to one-degree or less without computations?

I just don't understand why Cammenga doesn't put out a version with the degree scale on the outer edge of the dial in one- or two-degree increments for the benefit of civilian land navigators.

Then there is the issue of inherent accuracy. Brand-new, the G.I. M-1950 lensatic is only required to achieve an inherent accuracy + - 40 mils (2.25 degrees) from actual azimuth under milspec requirements. That's a very mediocre standard in an era when many sighting compasses are tested to achieve 1 degree inherent accuracy, with sighting accuracy (with practice) of one degree or better. Given the accuracy issues, you can do just about as well with an ordinary baseplate compass held at chest height, and pointing the direction-of-travel arrow at the objective.

That dry card housing can't ever form a bubble or leak. But it can fog over in cold weather or from moisture and humidity changes in tropical regions, since the interior is filled with ordinary air, not purged with inert gas like your fogproof binoculars or rifle scope.

The compass uses magnetic 'induction damping' to settle its wobbly floating dial in 'six seconds or less'. Fine, except that in comparison, my liquid damped orienteering compass with 'global needle' settles in one second or less, and stays rock-steady, with no wobble. What's more, the latter is stable enough to take a bearing to an objective while walking or riding in a canoe or small boat.

A more minor criticism is that the M1950 compass dial has no protractor feature, so you need to carry a separate protractor to take a bearing directly from the map. It has no romer scales, and only one 1:50,000 metric scale, which isn't much use for USGS 1:24,000 topos. It also has no adjustable declination feature for relating all compass headings to true north. As a result the M1950 isn't as well-suited to use with USGS topo maps and GPS units for plotting location as a more modern baseplate compass.

The compass itself is built with attention to detail and all parts on my example were well-fitted with no signs of manufacturing or assembly defects. Cammenga does an excellent job on meeting milspec standards. The luminous lighting on the standard model is excellent, once charged with a flashlight, but if you have a flashlight anyway, the luminous feature isn't really necessary.

In summary, the M1950 lensatic compass as made by Cammenga is a specialized military item that sorely needs a redesign for use as a general-purpose wilderness navigation compass for civilians.

Source: bought it new

Price Paid: $50

An accurate and tough compass that will give a lifetime of service. The Tritium won't, but this can be replaced by Cammenga every 13 years or so.

Pros

- Dry capsule will not develop bubbles.

- Accurate and dependable

- Can take rough use.

- Replaceable parts

Cons

- Tritium lifespan is 12-14 years, so the glowing dims about then

- Not a beginners compass, but not hard to master either.

I have used this compass for the past year but have tried out a phosphorescent version for some time. I use the 3H mainly for navigating at darker times as we move to lookout areas for early morning calling.

I do take it out on hikes and walks to keep skills up and really like the lensatic compasses for navigation. When they are quality built they are accurate and dependable. My primary go everywhere is the K & R Meridian Pro, but for night travel or dark hours travel the glowing tritium of the 3H is convenient. It is my backup compass.

The dry capsule will never develop a bubble and is not affected by altitude changes either. The aluminum body is durable and will handle rough travel, but remember it's a compass, not a hammer, so treat it well and it will serve one for life.

The lens is clear and the dial is not hard to read for me. I do have failing (aging) sight, but am still near 20/20. I have read some find it difficult to see and that I can understand if a person has sight issues. That is something to think about if you do.

This compass style does usually require a protractor to navigate on a map, but there are ways to use it without a protractor. The compass is accurate to 2.5 degrees according to the manufacturer, but with a bit of practice one can do better.

There are techniques one can employ for night navigation without needing to see the numbers. They involve using some math and the clicks of the bezel as you rotate it. Each "click" is 3 degrees. I have done it and it is accurate enough. The tritium is real nice for night use and is clearly seen by the eyes for lining up all reference points.

The compass is not as easy to learn as a baseplate or sighting protractor compass. With some basic instruction it can be learned with very little effort. It's not rocket science. Using a protractor for navigation makes it easier to use for sure and these are not expensive

When closed up the needle is locked in place and protected. This is a nice feature that extends needle life.

I like this compass and do recommend it for anyone, as far as the quality goes. That said, I don't think everyone would like this type of compass. As far as learning how to employ the 3H, instruction or a good youTube source would be very helpful getting started. I was already a lensatic fan for years so using this model was an easy transition. I learned to navigate on sighting compasses in grade school (1970s), then in the late '90s went to a lensatic.

I don't think this is a compass for everyone. It can be a little more difficult to learn on. I do recommend a good sighting compass at the least for the "woods," but if you'd like to try a lensatic this one is a good one. Durable, accurate, and not too terribly difficult to learn on.

Background

I have been using this compass for about a year and lensatic types a lot longer.

Source: bought it new

Price Paid: $90

Original Review: April 6, 2012

Well-made, but less than ideal for non-military users.

Pros

- Air-filled compass housing can't develop a bubble

- Self-luminous tritium lighting (in some models)

- Excellent manufacturing and assembly quality

- Deep-well compass housing for use in multiple magnetic zones

Cons

- Mediocre accuracy

- Mediocre shock resistance

- No protractor base for taking bearings from a map

- Degree scale in 5-degree increments only

- Can fog over in certain conditions

- Floating compass dial slow to settle

The U.S. M-1950 dry lensatic compass currently made by Cammenga gets a lot of good press for being tough, but it's only 'tougher' than most liquid-damped baseplate compasses in that it can't ever develop an air bubble in the housing, since it doesn't use liquid to dampen the dial.

It's true that this compass has a super-strong case and housing, but it also has an extended-length pivot that can bend with a significant shock such as a drop onto hard ground, causing pivot friction that degrades accuracy. Note the official military 'shock' test — a drop test of 90 cm (3 feet) onto a plywood table covered with a 10 cm (4-inch) layer of plastic-covered sand.

This compass is often praised for its superior accuracy over most baseplate style compass designs in shooting an azimuth (taking a bearing) to an objective or landmark. Let's examine that.

The compass dial is in both mils and degrees, and as the military uses mils, the degree scale is given second place on the dial. As a result, the degree scale is only marked in large five-degree increments — a dial you'd expect on a $10 compass, not one costing $50 or more.

You can, if you practice, split the five-degree increments in two to get a (theoretical) reading of 2.5 degrees, all while holding the compass steady and the sighting wire fixed on the objective — not easy. Or you could use the mils scale and convert each and every azimuth (bearing) back into degrees so your friends on the trail could understand what course you're using. But who's going to bother with that?

I just don't understand why Cammenga doesn't put out a version with the degree scale on the outer edge of the dial in one- or two-degree increments for the benefit of its civilian land navigators.

Then there is the issue of inherent accuracy. Brand-new, the G.I. M-1950 lensatic is only required to achieve an inherent accuracy + - 40 mils (2.25 degrees) from actual azimuth under milspec requirements. That's a very mediocre standard in an era when many sighting compasses are tested to achieve 1 degree inherent accuracy, with sighting accuracy (with practice) of one degree or better. Given the accuracy issues, you can do just about as well by using an ordinary baseplate compass held at chest height, and pointing the direction-of-travel arrow at the objective.

The compass uses magnetic 'induction dampening' instead of the more common liquid dampening used in many baseplate compasses, which is advertised as an advantage (no way to form air bubbles or leak). But what most people don't know is that the original M-1938 U.S. Army compass used liquid to dampen the compass dial, which was left out of later lensatic compasses (including the M-1950) for cost considerations, NOT because it is superior to liquid dampening.

Since it is filled with ordinary air, the M-1950 can and does fog over in cold weather or from moisture and humidity changes in tropical regions, since the interior is not purged with inert gas like your fogproof binoculars or rifle scope. Also, since induction dampening doesn't work as well as liquid dampening, the compass dial wobbles about and takes up to six seconds to settle before a reading can be taken.

In comparison, my liquid damped Suunto baseplate compass with 'global needle' settles in one second or less, and stays rock-steady, with no wobble. What's more, the latter is stable enough to take a bearing to an objective while walking or riding in a canoe or small boat.

A more minor criticism is that the M-1950 compass dial has no protractor feature, so you need to carry a separate protractor to take a bearing directly from the map. It has no romer scales, and only one 1:50,000 metric scale, which isn't much use for USGS 1:24,000 topos. It also has no adjustable declination feature for relating all compass headings to true north. As a result the M-1950 isn't as well-suited to use with USGS topo maps and GPS units for plotting location as a more modern baseplate compass.

The compass itself is built with attention to detail and all parts on my example were well-fitted with no signs of manufacturing or assembly defects. Cammenga does an excellent job on meeting milspec standards.

The tritium sighting is a great option for low light and the occasional emergency night hike, and should be available on other compass models here in the states (outside North America, anyone can buy a Silva of Sweden 4b or 54b Expedition military compass with beta, or tritium lighting). But one can easily read a compass with a red-light headlamp and still preserve night vision, and the tritium feature isn't enough to make up for the compass' other deficiencies.

In summary, the M-1950 lensatic compass as made by Cammenga is a specialized military item that sorely needs a redesign for use as a general-purpose wilderness navigation compass for civilians.

Update: April 6, 2012

Well-made, but less than ideal for non-military users.

Pros

- Air-filled compass housing can't develop a bubble

- Self-luminous tritium lighting

- Excellent manufacturing and assembly quality

- Deep-well compass housing for multiple magnetic zones

Cons

- Mediocre accuracy

- Mediocre shock resistance

- Degree scale in 5-degree increments only

- Can fog over in certain conditions

- Compass dial slow to settle

The U.S. M-1950 dry lensatic compass currently made by Cammenga in the 3H configuration is lauded as being the toughest, most accurate compass on the market. After all, the U.S. military uses it, so it must be the best, right? Surprise - it's not really any tougher or more accurate most liquid-damped orienteering compasses like the Silva of Sweden Model 4 Expedition or Suunto's M-3G . Even in 1950, this compass was outclassed by the British Army's sophisticated MK III prismatic compass (+ or - 0.5 degree accuracy). And in the civilian world, things have changed a lot since then.

It's true that Cammenga's version of the M-1950 compass has a super-strong case and housing, and can't develop an air bubble since it's a dry card (induction dampening) design. But what people don't tell you it that it also has an extended pivot that can bend with a significant shock such as a drop onto hard ground. Once the pivot is bent, the dial will not produce repeatable, accurate readings. Note the official military 'shock' test — an easy 'drop test' of 90 cm (3 feet) onto a table covered with a 10cm (4-inch) layer of plastic-covered sand.

The M-1950 lensatic compass design is also frequently extolled for its superior accuracy over most orienteering-style compass designs in shooting an azimuth (taking a bearing) to an objective or landmark. Let's examine that.

The compass dial is in both mils and degrees, and as the military uses mils, the degree scale is given second place on the dial. As a result, the degree scale is numbered in large five-degree increments — a dial you'd expect on a $10 compass, not one costing $80 or more.

You can, if you practice, split the five-degree increment spacing in half to get a (theoretical) reading of 2.5 degrees between increments, while simultaneously holding the compass steady and the sighting wire fixed on the objective, then checking for parallax error — not easy. Or you could use the mils scale and convert each and every azimuth (bearing) you take back into degrees for the benefit of your companions (all of whom will have degree scale compasses).

But why bother, when other compasses have easy-to-read dials that can be read to 1 degree or less with ease? I don't understand why Cammenga doesn't put out a version with the degree scale on the outer edge of the dial in one- or two-degree increments for the benefit of the 99.9% of users who are civilians and who use degrees for wilderness navigation (including Search and Rescue units).

Besides that, there is the issue of inherent accuracy. Brand-new, the G.I. M-1950 lensatic is only required to achieve an inherent accuracy of + - 40 mils (2.25 degrees) from actual azimuth (milspec). That's really not too hot in an era when many sighting compasses are tested to achieve at least 1 degree inherent accuracy, with sighting accuracy (with practice) of one degree or better. Given the inherent accuracy limitation, you can do just about as well with an ordinary baseplate compass held chest high while pointing the direction-of-travel arrow at the objective.

Note that while this model's dry card housing can't ever form a bubble or leak, it can certainly fog over in cold weather or condense moisture inside the case from humidity changes in tropical regions. Why? Because the interior is filled with ordinary air instead of an inert gas like your fogproof binoculars or rifle scope.

The compass uses magnetic 'induction dampening' to settle the floating dial in 'six seconds or less'. Fine, except that in comparison, my liquid dampened Suunto compass with 'global needle' settles in less than one second, and stays rock-steady, with no wobble. Because the latter is a gimbaled design, I can even take accurate compass readings while walking or riding in a small boat or canoe.

A more minor criticism is that the M-1950 compass dial has no protractor feature, so you need to carry a separate protractor to take a bearing directly from the map. It has no romer scales, and only one 1:50,000 metric scale, which isn't much use for USGS 1:24,000 topos. It also has no adjustable declination feature for relating all compass headings to true north. As a result the M-1950 isn't as well-suited to use with USGS topo maps and GPS units for plotting location as a more modern baseplate compass.

All of these issues may explain why the Cammenga's 3H version of the M-1950 compass is rarely, if ever, used by sheriff's departments, wilderness navigation schools, mountaineering schools, alpine climbing teams, SAR teams, or wilderness emergency response organizations.

The compass itself is built with attention to detail and all parts on my example were well-fitted with no signs of manufacturing or assembly defects. Cammenga does an excellent job on meeting milspec standards.

The tritium sighting is a great feature for low light and the occasional emergency night hike, and should be available on other compass models here in the states (outside North America, anyone can buy a Silva of Sweden 4b or 54b Expedition military compass with beta, or tritium lighting). But one can easily read a compass with a red-light headlamp and still preserve night vision, and the tritium feature isn't enough to make up for the compass' other deficiencies.

In summary, the M-1950 lensatic compass in 3H configuration as made by Cammenga is a special-purpose military compass that needs a redesign to compete as a general-purpose wilderness navigation compass.

Update: August 14, 2012

Well-made, but less than ideal for non-military users.

Pros

- Air-filled compass housing can't develop a bubble

- Excellent manufacturing and assembly quality

- Deep-well compass housing

Cons

- Mediocre accuracy

- Mediocre shock resistance

- Degree scale in 5-degree increments only

- Can fog over in certain conditions

- Wobbly, slow-to-settle compass dial

The U.S. M1950 dry lensatic compass currently made by Cammenga gets a lot of good press for being tough, but it's only 'tougher' than most liquid-filled baseplate compasses in that it can't ever develop an air bubble in the housing, since it doesn't use liquid to dampen the dial.

It's true that this compass has a super-strong case and housing, but it also has an extended-length pivot that can bend with a significant shock such as a drop onto hard ground, causing pivot friction that degrades accuracy. Note the official military 'shock' test — an easy 'drop' test of 90 cm (3 feet) onto a plywood table covered with a 10 cm (4-inch) layer of plastic-covered sand.

This compass is often praised for its superior accuracy over most baseplate style compass designs in shooting an azimuth (taking a bearing) to an objective or landmark. Let's examine that.

The compass dial is in both mils and degrees, and as the military uses mils, the mils scale is placed on the outside circumference of the dial, while the degree scale is in red ink and relegated to second place on the inside, with only five-degree increments or markings — a dial you'd expect on a $10 compass, not one costing $50 or more.

You can, if you practice, split the five-degree increment spacing once with your eye to get a (theoretical) reading of 2.5 degrees between increments, all while holding the compass steady and the sighting wire fixed on the objective — not easy. Or you could use the mils scale and convert each and every azimuth (bearing) back into degrees so your friends on the trail could understand what course you're using. But why bother, when there are other compasses out there with dials that can be easily interpolated to one-degree or less without computations?

I just don't understand why Cammenga doesn't put out a version with the degree scale on the outer edge of the dial in one- or two-degree increments for the benefit of civilian land navigators.

Then there is the issue of inherent accuracy. Brand-new, the G.I. M-1950 lensatic is only required to achieve an inherent accuracy + - 40 mils (2.25 degrees) from actual azimuth under milspec requirements. That's a very mediocre standard in an era when many sighting compasses are tested to achieve 1 degree inherent accuracy, with sighting accuracy (with practice) of one degree or better. Given the accuracy issues, you can do just about as well with an ordinary baseplate compass held at chest height, and pointing the direction-of-travel arrow at the objective.

That dry card housing can't ever form a bubble or leak. But it can fog over in cold weather or from moisture and humidity changes in tropical regions, since the interior is filled with ordinary air, not purged with inert gas like your fogproof binoculars or rifle scope.

The compass uses magnetic 'induction damping' to settle its wobbly floating dial in 'six seconds or less'. Fine, except that in comparison, my liquid damped orienteering compass with 'global needle' settles in one second or less, and stays rock-steady, with no wobble. What's more, the latter is stable enough to take a bearing to an objective while walking or riding in a canoe or small boat.

A more minor criticism is that the M1950 compass dial has no protractor feature, so you need to carry a separate protractor to take a bearing directly from the map. It has no romer scales, and only one 1:50,000 metric scale, which isn't much use for USGS 1:24,000 topos. It also has no adjustable declination feature for relating all compass headings to true north. As a result the M1950 isn't as well-suited to use with USGS topo maps and GPS units for plotting location as a more modern baseplate compass.

The compass itself is built with attention to detail and all parts on my example were well-fitted with no signs of manufacturing or assembly defects. Cammenga does an excellent job on meeting milspec standards. The luminous lighting on the standard model is excellent, once charged with a flashlight, but if you have a flashlight anyway, the luminous feature isn't really necessary.

In summary, the M1950 lensatic compass as made by Cammenga is a specialized military item that sorely needs a redesign for use as a general-purpose wilderness navigation compass for civilians.

Source: bought it new

Price Paid: $50

Original Review: April 6, 2012

Well-made, but less than ideal for non-military users.

Pros

- Air-filled compass housing can't develop a bubble

- Self-luminous tritium lighting (in some models)

- Excellent manufacturing and assembly quality

- Deep-well compass housing for use in multiple magnetic zones

Cons

- Mediocre accuracy

- Mediocre shock resistance

- No protractor base for taking bearings from a map

- Degree scale in 5-degree increments only

- Can fog over in certain conditions

- Floating compass dial slow to settle

The U.S. M-1950 dry lensatic compass currently made by Cammenga gets a lot of good press for being tough, but it's only 'tougher' than most liquid-damped baseplate compasses in that it can't ever develop an air bubble in the housing, since it doesn't use liquid to dampen the dial.

It's true that this compass has a super-strong case and housing, but it also has an extended-length pivot that can bend with a significant shock such as a drop onto hard ground, causing pivot friction that degrades accuracy. Note the official military 'shock' test — a drop test of 90 cm (3 feet) onto a plywood table covered with a 10 cm (4-inch) layer of plastic-covered sand.

This compass is often praised for its superior accuracy over most baseplate style compass designs in shooting an azimuth (taking a bearing) to an objective or landmark. Let's examine that.

The compass dial is in both mils and degrees, and as the military uses mils, the degree scale is given second place on the dial. As a result, the degree scale is only marked in large five-degree increments — a dial you'd expect on a $10 compass, not one costing $50 or more.

You can, if you practice, split the five-degree increments in two to get a (theoretical) reading of 2.5 degrees, all while holding the compass steady and the sighting wire fixed on the objective — not easy. Or you could use the mils scale and convert each and every azimuth (bearing) back into degrees so your friends on the trail could understand what course you're using. But who's going to bother with that?

I just don't understand why Cammenga doesn't put out a version with the degree scale on the outer edge of the dial in one- or two-degree increments for the benefit of its civilian land navigators.

Then there is the issue of inherent accuracy. Brand-new, the G.I. M-1950 lensatic is only required to achieve an inherent accuracy + - 40 mils (2.25 degrees) from actual azimuth under milspec requirements. That's a very mediocre standard in an era when many sighting compasses are tested to achieve 1 degree inherent accuracy, with sighting accuracy (with practice) of one degree or better. Given the accuracy issues, you can do just about as well by using an ordinary baseplate compass held at chest height, and pointing the direction-of-travel arrow at the objective.

The compass uses magnetic 'induction dampening' instead of the more common liquid dampening used in many baseplate compasses, which is advertised as an advantage (no way to form air bubbles or leak). But what most people don't know is that the original M-1938 U.S. Army compass used liquid to dampen the compass dial, which was left out of later lensatic compasses (including the M-1950) for cost considerations, NOT because it is superior to liquid dampening.

Since it is filled with ordinary air, the M-1950 can and does fog over in cold weather or from moisture and humidity changes in tropical regions, since the interior is not purged with inert gas like your fogproof binoculars or rifle scope. Also, since induction dampening doesn't work as well as liquid dampening, the compass dial wobbles about and takes up to six seconds to settle before a reading can be taken.

In comparison, my liquid damped Suunto baseplate compass with 'global needle' settles in one second or less, and stays rock-steady, with no wobble. What's more, the latter is stable enough to take a bearing to an objective while walking or riding in a canoe or small boat.

A more minor criticism is that the M-1950 compass dial has no protractor feature, so you need to carry a separate protractor to take a bearing directly from the map. It has no romer scales, and only one 1:50,000 metric scale, which isn't much use for USGS 1:24,000 topos. It also has no adjustable declination feature for relating all compass headings to true north. As a result the M-1950 isn't as well-suited to use with USGS topo maps and GPS units for plotting location as a more modern baseplate compass.

The compass itself is built with attention to detail and all parts on my example were well-fitted with no signs of manufacturing or assembly defects. Cammenga does an excellent job on meeting milspec standards.

The tritium sighting is a great option for low light and the occasional emergency night hike, and should be available on other compass models here in the states (outside North America, anyone can buy a Silva of Sweden 4b or 54b Expedition military compass with beta, or tritium lighting). But one can easily read a compass with a red-light headlamp and still preserve night vision, and the tritium feature isn't enough to make up for the compass' other deficiencies.

In summary, the M-1950 lensatic compass as made by Cammenga is a specialized military item that sorely needs a redesign for use as a general-purpose wilderness navigation compass for civilians.

Update: April 6, 2012

Well-made, but less than ideal for non-military users.

Pros

- Air-filled compass housing can't develop a bubble

- Self-luminous tritium lighting

- Excellent manufacturing and assembly quality

- Deep-well compass housing for multiple magnetic zones

Cons

- Mediocre accuracy

- Mediocre shock resistance

- Degree scale in 5-degree increments only

- Can fog over in certain conditions

- Compass dial slow to settle

The U.S. M-1950 dry lensatic compass currently made by Cammenga in the 3H configuration is lauded as being the toughest, most accurate compass on the market. After all, the U.S. military uses it, so it must be the best, right? Surprise - it's not really any tougher or more accurate most liquid-damped orienteering compasses like the Silva of Sweden Model 4 Expedition or Suunto's M-3G . Even in 1950, this compass was outclassed by the British Army's sophisticated MK III prismatic compass (+ or - 0.5 degree accuracy). And in the civilian world, things have changed a lot since then.

It's true that Cammenga's version of the M-1950 compass has a super-strong case and housing, and can't develop an air bubble since it's a dry card (induction dampening) design. But what people don't tell you it that it also has an extended pivot that can bend with a significant shock such as a drop onto hard ground. Once the pivot is bent, the dial will not produce repeatable, accurate readings. Note the official military 'shock' test — an easy 'drop test' of 90 cm (3 feet) onto a table covered with a 10cm (4-inch) layer of plastic-covered sand.

The M-1950 lensatic compass design is also frequently extolled for its superior accuracy over most orienteering-style compass designs in shooting an azimuth (taking a bearing) to an objective or landmark. Let's examine that.

The compass dial is in both mils and degrees, and as the military uses mils, the degree scale is given second place on the dial. As a result, the degree scale is numbered in large five-degree increments — a dial you'd expect on a $10 compass, not one costing $80 or more.

You can, if you practice, split the five-degree increment spacing in half to get a (theoretical) reading of 2.5 degrees between increments, while simultaneously holding the compass steady and the sighting wire fixed on the objective, then checking for parallax error — not easy. Or you could use the mils scale and convert each and every azimuth (bearing) you take back into degrees for the benefit of your companions (all of whom will have degree scale compasses).

But why bother, when other compasses have easy-to-read dials that can be read to 1 degree or less with ease? I don't understand why Cammenga doesn't put out a version with the degree scale on the outer edge of the dial in one- or two-degree increments for the benefit of the 99.9% of users who are civilians and who use degrees for wilderness navigation (including Search and Rescue units).

Besides that, there is the issue of inherent accuracy. Brand-new, the G.I. M-1950 lensatic is only required to achieve an inherent accuracy of + - 40 mils (2.25 degrees) from actual azimuth (milspec). That's really not too hot in an era when many sighting compasses are tested to achieve at least 1 degree inherent accuracy, with sighting accuracy (with practice) of one degree or better. Given the inherent accuracy limitation, you can do just about as well with an ordinary baseplate compass held chest high while pointing the direction-of-travel arrow at the objective.

Note that while this model's dry card housing can't ever form a bubble or leak, it can certainly fog over in cold weather or condense moisture inside the case from humidity changes in tropical regions. Why? Because the interior is filled with ordinary air instead of an inert gas like your fogproof binoculars or rifle scope.

The compass uses magnetic 'induction dampening' to settle the floating dial in 'six seconds or less'. Fine, except that in comparison, my liquid dampened Suunto compass with 'global needle' settles in less than one second, and stays rock-steady, with no wobble. Because the latter is a gimbaled design, I can even take accurate compass readings while walking or riding in a small boat or canoe.

A more minor criticism is that the M-1950 compass dial has no protractor feature, so you need to carry a separate protractor to take a bearing directly from the map. It has no romer scales, and only one 1:50,000 metric scale, which isn't much use for USGS 1:24,000 topos. It also has no adjustable declination feature for relating all compass headings to true north. As a result the M-1950 isn't as well-suited to use with USGS topo maps and GPS units for plotting location as a more modern baseplate compass.

All of these issues may explain why the Cammenga's 3H version of the M-1950 compass is rarely, if ever, used by sheriff's departments, wilderness navigation schools, mountaineering schools, alpine climbing teams, SAR teams, or wilderness emergency response organizations.

The compass itself is built with attention to detail and all parts on my example were well-fitted with no signs of manufacturing or assembly defects. Cammenga does an excellent job on meeting milspec standards.

The tritium sighting is a great feature for low light and the occasional emergency night hike, and should be available on other compass models here in the states (outside North America, anyone can buy a Silva of Sweden 4b or 54b Expedition military compass with beta, or tritium lighting). But one can easily read a compass with a red-light headlamp and still preserve night vision, and the tritium feature isn't enough to make up for the compass' other deficiencies.

In summary, the M-1950 lensatic compass in 3H configuration as made by Cammenga is a special-purpose military compass that needs a redesign to compete as a general-purpose wilderness navigation compass.

Update: August 14, 2012

Well-made, but less than ideal for non-military users.

Pros

- Air-filled compass housing can't develop a bubble

- Excellent manufacturing and assembly quality

- Deep-well compass housing

Cons

- Mediocre accuracy

- Mediocre shock resistance

- Degree scale in 5-degree increments only

- Can fog over in certain conditions

- Wobbly, slow-to-settle compass dial

The U.S. M1950 dry lensatic compass currently made by Cammenga gets a lot of good press for being tough, but it's only 'tougher' than most liquid-filled baseplate compasses in that it can't ever develop an air bubble in the housing, since it doesn't use liquid to dampen the dial.

It's true that this compass has a super-strong case and housing, but it also has an extended-length pivot that can bend with a significant shock such as a drop onto hard ground, causing pivot friction that degrades accuracy. Note the official military 'shock' test — an easy 'drop' test of 90 cm (3 feet) onto a plywood table covered with a 10 cm (4-inch) layer of plastic-covered sand.

This compass is often praised for its superior accuracy over most baseplate style compass designs in shooting an azimuth (taking a bearing) to an objective or landmark. Let's examine that.

The compass dial is in both mils and degrees, and as the military uses mils, the mils scale is placed on the outside circumference of the dial, while the degree scale is in red ink and relegated to second place on the inside, with only five-degree increments or markings — a dial you'd expect on a $10 compass, not one costing $50 or more.

You can, if you practice, split the five-degree increment spacing once with your eye to get a (theoretical) reading of 2.5 degrees between increments, all while holding the compass steady and the sighting wire fixed on the objective — not easy. Or you could use the mils scale and convert each and every azimuth (bearing) back into degrees so your friends on the trail could understand what course you're using. But why bother, when there are other compasses out there with dials that can be easily interpolated to one-degree or less without computations?

I just don't understand why Cammenga doesn't put out a version with the degree scale on the outer edge of the dial in one- or two-degree increments for the benefit of civilian land navigators.

Then there is the issue of inherent accuracy. Brand-new, the G.I. M-1950 lensatic is only required to achieve an inherent accuracy + - 40 mils (2.25 degrees) from actual azimuth under milspec requirements. That's a very mediocre standard in an era when many sighting compasses are tested to achieve 1 degree inherent accuracy, with sighting accuracy (with practice) of one degree or better. Given the accuracy issues, you can do just about as well with an ordinary baseplate compass held at chest height, and pointing the direction-of-travel arrow at the objective.

That dry card housing can't ever form a bubble or leak. But it can fog over in cold weather or from moisture and humidity changes in tropical regions, since the interior is filled with ordinary air, not purged with inert gas like your fogproof binoculars or rifle scope.

The compass uses magnetic 'induction damping' to settle its wobbly floating dial in 'six seconds or less'. Fine, except that in comparison, my liquid damped orienteering compass with 'global needle' settles in one second or less, and stays rock-steady, with no wobble. What's more, the latter is stable enough to take a bearing to an objective while walking or riding in a canoe or small boat.

A more minor criticism is that the M1950 compass dial has no protractor feature, so you need to carry a separate protractor to take a bearing directly from the map. It has no romer scales, and only one 1:50,000 metric scale, which isn't much use for USGS 1:24,000 topos. It also has no adjustable declination feature for relating all compass headings to true north. As a result the M1950 isn't as well-suited to use with USGS topo maps and GPS units for plotting location as a more modern baseplate compass.

The compass itself is built with attention to detail and all parts on my example were well-fitted with no signs of manufacturing or assembly defects. Cammenga does an excellent job on meeting milspec standards. The luminous lighting on the standard model is excellent, once charged with a flashlight, but if you have a flashlight anyway, the luminous feature isn't really necessary.

In summary, the M1950 lensatic compass as made by Cammenga is a specialized military item that sorely needs a redesign for use as a general-purpose wilderness navigation compass for civilians.

Source: bought it new

Price Paid: $50

Very well built, impressive compass, at least until the lens fell out.

Pros

- Appears tough

- Mostly very well made

Cons

- The lens fell out

- Bulky

I bought two of these compasses over the years. The first one I lost on a hunting trip, and when I went back to look for it, well, the olive drab paint is difficult to spot in the grass. Take that as a plus or minus, depending on your perspective.

The second one I bought I used for all types of activities. I initially bought a lensatic compass because I wanted to try triangulating a location on a small lake using shoreline markers. It worked well for that.

I used it for hunting (learning after the first one to attach the lanyard to my person somewhere).

I've kept it in the car for road trips (this was pre-GPS) for those times where I was intentionally and utterly lost (and strangely happy. But that's a story for later). It worked well enough for that.

I've never actually used it for any military or assault type purposes. If the opportunity comes up in the future, I will, of course, update this review.

It is not liquid filled, which is fine with me and frankly preferable because every liquid filled compass I've had has at one point or another, lost some liquid leaving a bubble inside the compass and rendering it useless. It has a dampening system, so it settles down relatively quick. The interior is white.

Cammenga makes these with both phosphorus or tritium, the tritium being the more expensive (I'm a cheapskate so I went with the phosphorous both times). It holds its "charge" pretty good.

It is bulky. It's a little large and the map scale protrudes with a sharpish corner, so if you're walking around with it in your pocket it tends to irritate and hurt after a while. Structurally, it's held up great. It's taken some abuse, some drops, being knocked around, etc.

The sighting lens recently fell out, however. I'm not sure how it happened. I lent it to my son and he returned it missing the lens. He didn't notice it missing of course, but it shouldn't have been a big deal. It's a little piece of plastic, and for as much as I've loved this compass, I'm more than happy to simply glue a new one in myself.

I called Cammenga and asked them how I can get a new lens. They told me it would cost $60 to replace the lens. I paid $70 for the bloody compass.

I like the compass, but I'm extremely dissatisfied with the Cammenga.

Source: bought it new

Price Paid: Around $70

Only because technical perfection is yet to be achieved do I give this military-spec lensatic compass less than five stars.

As another reviewer has mentioned, its case is as sturdy as can be imagined for a hand-held compass, being machined of aluminum to house the compass workings. Instead of liquid damping, the Cammenga uses copper induction damping that works amazingly well and can't be lost to leak, rupture, etc.--as happened to my old Silva Ranger that I bought this to replace.

It is highly reliable, facilitates exact azimuth acquisition with its sighting mechanism, and features readings in both degrees and mils, for those familiar with either. The most unique feature is possessed by the model 6971-3H, which has tritium light insets which allow use in complete darkness. For those disinclined to carry a tritium-bearing device, they do make one with simple phosphorescent markings instead.

Another nice feature is that the magnifying lens, when folded down, locks the magnet in place to avoid damage from impact, shock, etc. The compass also comes with a nylon carry case, a lanyard, and belt clip for the case, as well as a brief instruction manual written in very direct military style.

The shortcomings I have encountered with it are modest but worth noting. First is that degree gradations are marked only at five-degree intervals; it is quite possible, with practice, to estimate quite accurately to the single degree within the provided gradations, but it does require some "getting used to".

The second quibble is that the scale markings along the straight edge available when the compass is completely open are suitable for 1:50,000 scale markings, but some of the markings (specifically, those for 2000 and 4000 m) aren't marked so as to quickly distinguish them from neighboring marks.

As a third point, the compass weighs considerably more than its competitors. For the gram-counters out there, this is NOT their compass of choice. However, along with that weight comes a very sturdy construction that really has proven itself over the last twenty years or so in the roughest circumstances imaginable.

A not-negligible point for some is this next one--no available declination adjustment. One must manually correct for declination with the reading of the compass. While not difficult for an experienced user, someone who is used to setting declination and forgetting it thereafter will have to be reminded occasionally to make the proper adjustment in sighting.

And, finally, it has no mirror. Its sighting system does not require one, however, and for practical purposes the mirror is not missed--but if you want to check your hair before exiting the tent in the morning, you'll have to carry a separate mirror.

Price Paid: $79.99

I have used the milspec/issue Tritium H3 clam since 1979. 4 stars for accuracy and occasional pivot point/card slip, but for the $, it's great. Lasts about 10-12 years, then donated to scouts.

Also used the Pyser M-73 (degrees) Black Liquid Prismatic Compass and MILS a lot in locations not friendly to U.S. It too is 5 stars.

Pros

- Universal use, not identified as U.S. gear

Cons

- No tritium

A great compass.

Beware of Amazon and eBay knockoffs. If it's a life support kit, DO NOT skimp.

Source: bought it new

Price Paid: $150

I have done land navigation at many different places around the world. Many were unpleasant where accuracy was/is critical. As a cavalry scout the ability to have excellent land navigation skills is a must.

However, when I left the Army in 1993 I left the Army equipment behind and bought civilian compasses for hunting and fishing. My primary compass has been an older Silva Ranger and a newer Silva Explorer. They have have been good solid compasses which is more than adequate for what I have been doing.

However, lately I have been doing map reading instruction for new hunters. I wanted something more dependable than my old standby - the Silva's. So I asked for a Cammenga 3H (basic Army compass)for Christmas.

What a difference! First, off it was like coming home again. Everything just felt right about it.

Secondly, the ability to easily navigate in really difficult terrain is far better and more accurate. With the thumbhole holder it is easier to level.

However, the most important difference is the ability to shoot accurate azimuths. The Silva was good but the 3H is far better. I like the locking card, the tritium dial and the maginifier. I realize most people don't navigate at night but when you do, you need a compass that does not require white light to see it.

Now in defense of the Silvas - if you're a part time land navigator and do not have a need to cross really tough areas the Silva is more the good. However, if you're going to navigate in situations that could end up being survival situations, spring for the 3H.

What kind of situations are those? Well, skiing/snowmobiling in back country areas far from any man made land marks (no Virginia, they don't have cell phone coverage out there!). Low areas where you must constantly shoot accurate azimuths, etc.

Just a word of caution. Most people will waste there money if they buy a 3H. It is much more than most people need. In fact a Silva Explorer is perfect for most backpackers, etc. However, if you really want the most dependable, accurate and tough personal compass this is it.

Price Paid: Gift

Durable and accurate.

Pros

- Easy to read

- Accurate

Cons

- Heavier than most.

I bought one of these as a replacement for an old Silva compass. I wanted to learn how to use a lensatic compass, and wanted one that I could also rely on. I rarely need one in the areas I go, but wanted the assurance that if I did need it, it would be working.

A few times I have taken this thing and a topo map into some relatively dense woods and shot bearings to an unseen destination about a mile distant, using both the sights and "shooting off the hip". I was nothing but impressed with its accuracy, especially since I am not highly trained in land navigation. I had my GPS also, but buried it in my pack to prevent cheating.

Once I downloaded the track to my PC I was surprised how straight the navigation was, including four 90 degree turns 100 to 200 yards apart to route myself around a swamp. (Walking a straight line in any forest with no clear target in sight is always a challenge.)

I think the biggest benefit of this compass is how easy it is to read and follow a bearing. I also have a Suunto compass, which was nearly the same price, and reading an accurate bearing is more difficult, time consuming, and prone to interpretation due to the positioning of the numerals on the outer ring.

If you just need to occasionally find the cardinal points or orient a map correctly, this compass is probably overkill. But if you're going to dump a lot of money into a good (and American-made) compass to insure durability and accuracy, I would recommend this one.

Source: bought it new

Price Paid: $79.95

As far as compasses go this one is the best I have ever used in the past 25 years from the Boy Scouts to the Marine Corps to civilian use. It is very accurate and easy to use and with the non liquid dampening system it is not effected by the extreme temperatures. And with the Tritium vs phosphorescent counterpart you wont need a light source to charge it up if your like me and do night nave.

Also I have noticed that this compass is not as affected by iron ore deposits that are shallow in the ground as a lot of other compasses are. It is a bit heaver than you average compass but it worth the extra weight for a piece of mind

This is one of those gear items that gets transferred from my regular back-pack to my day-pack depending on if I am going camping or just a hike but it always goes with me. I would definitely recommend either one of these compasses to any one.

The 3HC model is Tritium and the luminescent never need charging for ten years then you replace it (note the compass will work just fine but with no or little luminescent)

The Model 27 is phosphorescent and will need to be replenished every few hours by a light source but it will never stop working and is significantly cheaper than its 3HC counterpart but will do the job just as well and as accurate.

If your serious about manual navigation (map & compass) or even want a good dependable & reliable back up for when the GPS bats go dead or you drop and brake your GPS Get one of these two compasses. You cant beat the reliability.

Price Paid: $79

Way too inaccurate.

Pros

- Rugged

- Easy to use

- Compact

Cons

- TOO INACCURATE

Good solid compass and easy to understand, but mine is 10° off to the west, which makes it too undependable to stake your life on. Cammenga says they'll repair it for $50??? Really? A new compass?

Background

Extensive hiking and hunting using topo maps.

Source: bought it new

For some reason...I'm the very first member to review this compass. I've always been a major fan of this compass. It's the standard issue military compass. The model has tritium inserts and appears to be made of aluminum.

The cross hair style lensatic compass is EXTREMELY accurate. I've even successfully started a fire with the small magnetic lense.

No compass can match its durability. I once dropped a Silva compass (plastic) from about 4 feet and it shattered! Plastic is very cheap for the companies to construct a compass from. It was about -32 F. out that day. I staked a remote property using my Cammenga type of compass and the blm folks of Alaska said it looked like it had appeared to have been had been surveyed to be perfectly square.

This compass is expensive but will never fail. The only issue I have with this compass is the olive-drab paint. It is chipping off on the corners. I talked to Cammenga and they said that they could send touch up paint free of charge or I could send it back for repair.

Price Paid: 90 dollars

Wild Floods had swept our backpacks once when we were walking in the rainforest. 2 compass were with us, a European baseplate one and a 3h Cammenga one.

The baseplate was broken from a few drops, while the Cammenga was with us throughout the walks and has helped us back to the main camp.

Cammenga is very rugged and can stand all abuses we had during our lost. It was once thrown to a large king cobra approaching to our fires. Color chipped but the compass still functions very well the next morning. At present all of us are carrying one 3H to all our outings.

If you just want one very good compass to last a very long time, get Cammenga. Easy reading too. Invest just once and for all.

Price Paid: Second One US $52

This compass is built like a tank. It is extremely durable and accurate. It finds north quickly and consistently. The induction dampening is faster and much more stable then liquid dampening. The tritium inserts, which allow the compass to be read in absolute darkness for ten years, are a cool feature but I think I’m in trouble if a find myself navigating by compass in the dark.

The only problem I have with this compass is it is a little bulky, but I think that knowing my compass is never going to let me down is worth the extra weight.

Price Paid: $66

Your Review

Where to Buy

You May Like

Specs

| Price |

Current Retail: $104.25-$124.12 Historic Range: $94.50-$124.12 Reviewers Paid: $52.00-$150.00 |

| Accuracy |

+/- 40 mils |